The Art of Rehabilitation: A Conversation with Incarcerated Artists

- Stacey Putka

When I consider the intersection of art and labor, I am drawn to the concept of humanity. As humans, we strive for alignment in our lives. It isn’t easy to find a balance between pursuing one’s passions and making a living. We can all empathize with the romance novelist who doubles as a waiter to make ends meet or the sculptor who abandons their love of clay to work on Wall Street. Our need to support ourselves and our families often trumps our desire to pursue our passions. How do we ensure that a lifetime of meaningful work is also accompanied by a paycheck? If we are lucky, we train ourselves to identify the art within our labor, and over time our labor becomes art in motion, helping us to express our right to be seen as fully human.

As a society, regrettably, we often use dehumanizing language to remove this right from marginalized populations and—in doing so—block their path to the pursuit of happiness. At Breakthrough, formerly Defy Colorado, we work to restore this right to those who have been stripped of it by the criminal justice system. In the minds of the general public, the prison environment and experience is grossly oversimplified as “a bad place for bad people.” This could not be further from the truth. At Breakthrough we are redefining the purpose of prison and training community members like you to think about it differently.

Ending mass incarceration is a cause that we can all get behind. It’s expensive and ineffective, and it currently segregates over 2.2 million people from our communities. Instead, let’s choose to be vulnerable, to experience uncomfortable emotions, and to see the humanity of those who are living behind prison walls. Prisons should be rehabilitation centers where people can work to understand their personal values, develop skills in line with those values, and train to transfer those skills into careers.

I have met, interacted with, and been transformed by over two hundred people currently incarcerated in Colorado. These individuals carry their values close to their hearts and express them in some of the most beautiful artistic forms I have ever seen. Many of them have honed a valuable craft that could translate into a career, but barriers remain that prevent individuals with criminal histories from getting jobs once they are released. Knowledge is power, and learning about people who are currently or formerly incarcerated helps us dismantle biases and broaden our understanding of the intersection of art, labor, and prison.

Earlier this year, I sat down with four such artists to ask them about their experiences, and the process of growing through artmaking.

Meet the Artists

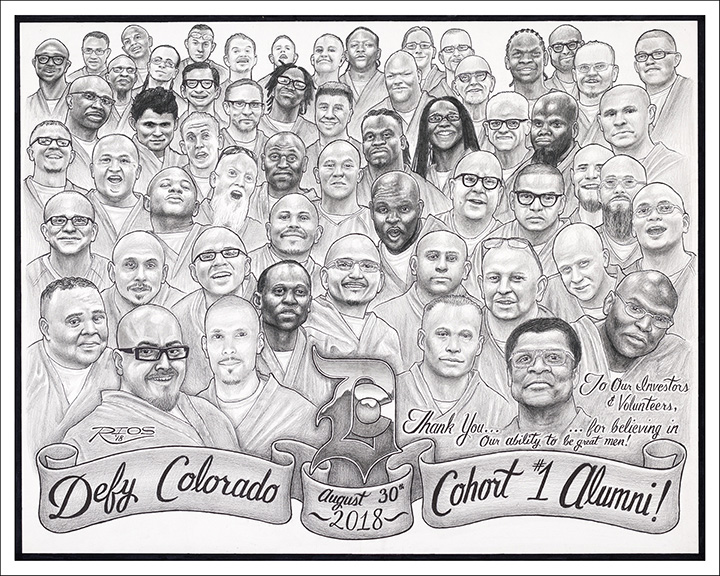

Rios is an artist. His mediums include graphite, acrylic paint, canvas, murals, wood carving, cake, and frosting. He draws, paints, tattoos, and bakes. His creativity has grown ever since the age of two when he picked up a crayon and scribbled on his grandma’s walls.

Miguel is an artist. His mediums include wood, laminate, metal, and bolts. He learned to build furniture in Arkansas Valley Correctional Facility.

Joybelle is an artist. Her mediums include writing and public speaking. She began her artistic practice in 2019 in La Vista Correctional Facility.

Nick is an artist. His mediums include JavaScript, PHP, and Python. He began learning to code in 2005 at MSU Denver and Arkansas Valley Correctional Facility.

Art in Motion

How did you develop the passion you have for your craft?

Rios: “As a kid, I could always keep myself busy with a pad of paper, some crayons, or a pencil, and use my imagination to create anything my little mind could conceive, which was mostly cartoons. Over the years, I would discover other forms of art and the artists who created them, everyone from Jim Davis (Garfield) to Stan Lee (Marvel), Bob Ross, Boris Vallejo, Luis Royo, and Coop. I [am] also…fascinated by the world of Goya, Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Monet, and M.C. Escher. I have learned a lot from these old masters, observing how they used their colors, light and shade, and perspective. Through all their influences and my continued self-taught, trial-and-error techniques, I have developed my own style that continues to evolve and push the envelope of my art.”

Miguel: “Developing my passion [for] the crafts, unlearning mercifully, and learning plenteously, came with sacrifice. In the early 1990s, Denver, Colorado was experiencing both crack cocaine and [a] gang epidemic. Immediate economic wealth through the drug market was a means for everyone that desired to elevate their poverty status. A 6 p.m. curfew was mandated by authorities to counteract record-high violence in the city. Although my fragile mind was incapable of articulating the contradictions I saw, I chose to inhale the[se] moral pollutants and utilize…my qualities to survive. Unable to choose my consequences, incarceration with no hope to reenter society became my reality. Indeed, I was deemed an [ir]redeemable person, but I learned how true mercy works, although feeling unworthy of mercy. My community began to invest into my illiteracy, apathy, generation[al and] cultural iconoclasm. I experienced compassion for the first time, which led to my personal commitment to no longer live in a comfort zone requiring no intellectual rigor and non-spiritual enrichment. Studying, praying, and socializing amongst different cultures became my noble reality. Since [then], my skill set has enhanced and has become transferable to society.”

Joybelle: “I never thought I was particularly articulate. I loved to read, learning at the age of three, and always preferr[ed] a book to playing outside. As a youngster, I had been encouraged in more musical directions. Coming to prison for the second time gave me the opportunity to really focus on the [self-]worth issues that were negatively impacting every facet of my life, from [my] career to relationships. As strange as it may sound, I’m grateful for the opportunities that I had access to while incarcerated. Without [them], I would never have met the volunteers from Breakthrough or the University of Denver Prison Arts Initiative (DU PAI), to name just two. The freedom that writing gave me, coupled with…positive reinforcement, inspired me to continue and to want to do so much more with my writing.”

Nick: “Honing my coding skills in prison was a blessing. What I originally viewed as a highly technical skill began to grow into something more creative. As I began to grasp the concepts of programming, I realized that there is rarely a ‘wrong’ answer when your program consistently produces the desired outcome. This has enabled me to solve difficult problems in fun and even elegant ways. Ultimately, building complex tools with nothing more than keystrokes and imagination allowed my mind to grow positively in an environment rampant with boredom and negativity.”

What does your craft mean to you and others?

Rios: “My craft is a way for me to meditate and analyze the direction my life has taken as well as where I am going and the legacy that I will leave. Because of the many forms of art I produce and the mediums I am adept in, I have been able to take care of myself and have a business selling my art to corrections officers.”

Miguel: “To me, unlearning is the process of challenging the paradigm that enables you to become conscious of your unconscious self. Learning is the process of consciously seeking knowledge [and] guidance, and comprehending how to apply the new information.”

Joybelle: “Writing provides a voice. It shares an experience and allows someone else to walk in your shoes, for a brief moment. It builds empathy and both educates and inspires.”

Nick: “Thanks to the internet, my craft allows me to join forces with programmers around the world to collaborate on projects that benefit everyone. I have also come to appreciate the strong community that exists among programmers. I have never approached a fellow programmer for advice and come away empty-handed.”

How has your craft changed you?

Rios: “As my art has gotten better, it [has become] a reflection of my growth in character to be a better human being.”

Miguel: “By no means am I a self-[made] man. Hope and compassion gave me the strength to pursue the aligning of my values with my purpose, which has made me another exceptional irredeemable person [who has been] rehabilitated.”

Joybelle: “Writing has allowed me to express deeply hidden truths and…to safely explore much of the trauma that molded so much of my experience. It has created a harbor to safely remove those masks and illuminate the shining soul that was buried so deeply, I had forgotten who I was meant to be.”

Nick: “Learning to code has completely changed the way I see the world. I now tackle most of life’s obstacles as if they were programming tasks. By mentally breaking large projects into smaller, more manageable pieces, it is easier to spot trouble before it starts.”

I would like to express my gratitude to Rios, Miguel, Joybelle, and Nick for sharing their perspectives with me and with you. Getting to know these four people and other incarcerated individuals has compelled me to work to end ineffective mass incarceration and redefine post-prison opportunities for those impacted by this problematic system. Conducting these interviews helped me to understand how the arts can serve as an impetus for self-reflection, rehabilitation, and economic opportunity. My mission–and the mission of Breakthrough–is to encourage this kind of rehabilitation for all. Criminal justice reform is personal. For me. For these artists. And for you.